High-quality audits of financial statements are essential to strong organizations, financial markets and economies. While audits have historically focused on enhancing the confidence of investors and other providers of capital, other stakeholders also benefit—including directors, management, employees, analysts, regulators, rating agencies, customers, suppliers, and the general public. Acknowledging this context, high-quality audits clearly serve the public interest.

Important conversations are taking place worldwide about corporate reporting, audit quality, stakeholder expectations, and corporate governance.1 It is critical that policy makers adopt a balanced and evidence-based perspective that recognizes the overall, and long-established success of audit, while effectively and proportionately remediating any shortcomings in a spirit of continuous improvement.

Achieving high-quality audits requires a well-functioning ecosystem built upon ethics and independence, preconditions to achieving high-quality audits. This ecosystem involves a number of factors and participants including the right people, the right governance, and the right regulation. These elements must all work together to produce the right audit that meets the expectations of stakeholders. The quality of audit must be assessed by the right measurements. In the absence of any of these components, the audit may not meet the expectations of stakeholders.2

All participants in the audit and assurance ecosystem must act to improve the audit process, the skill-set and mind-set of accounting professionals, the governance activities of companies and firms, the regulations and standards that support entity reporting and auditor behavior, and how audit quality is assessed.

Translation Available in

1. The Right Process

The objective of an audit is to provide investors and other stakeholders with reasonable assurance as to whether the financial statements, taken as a whole, are prepared in accordance with the applicable financial reporting framework and are free from material misstatement. Audits help directors and others responsible for oversight of a reporting entity to assess the robustness of the financial information prepared by management and obtain critical insights into an entity’s financial controls and associated risks. Audit and assurance services have evolved—and they must continue to do so—in order to meet the ever-changing needs of stakeholders.

- IFAC believes that audit stakeholders—particularly company boards, governing bodies, and management—should view audit as a value-added process rather than a compliance exercise that simply results in an audit opinion on the financial statements. Through the process of conducting the audit, the work of management in preparing reported information is examined. The process should enhance confidence in the assessment of risks, estimates and valuations, internal controls, data gathering, and how management is held accountable. We support efforts that enable the auditor to deliver greater transparency and value in the audit report—for example, requirements to communicate Key Audit Matters (under ISA 701)3 and Critical Audit Matters (under PCAOB AS 3101)4.

- IFAC believes that the use of technology should enable high-quality audits. Technology-driven tools can facilitate a more comprehensive examination of virtually all transactions and significantly increase the efficiency and effectiveness of audits. Applying technology to audit methodology can enhance the identification and analysis of high-risk matters that require specialized expertise. However, the application of technology to audit is unlikely, on its own, to lead to providing more than “reasonable assurance” nor always lead to the detection of fraud. Standard setters must continue to progress work that addresses advancements in, and the use of technology by audited entities, as well as how automated tools and techniques can be used in audit and assurance engagements5.

- We embrace the evolution of assurance services that better meet the needs of investors and a wider stakeholder group6, —including assurance of internal controls and risk management systems, fraud detection or forensic reviews, forward looking / going concern assessments (including ability to pay dividends), digital reporting, “non-GAAP” metrics, and reports or disclosures that enhance corporate reporting (including information reported under the International Integrated Reporting Framework).7 As the market need for these services evolves, and frameworks for the provision and assurance of such information are developed, organizations should benefit from these assurance engagements and regulators should consider what level of oversight and assurance is appropriate.

1 Several jurisdictions (e.g., Australia, South Africa, Netherlands, United Kingdom) are conducting reviews focused on various aspects of corporate reporting as well as the assurance of reported information.

2 This IFAC Point of View is relevant to achieving high-quality audits for private and public sector organizations—both large and small—but has particular relevance to Public Interest Entities (“PIEs”).

3 ISA 701 Communicating Key Audit Matters is the independent Auditor’s Report is effective for audits of financial statements for periods ending on or after December 15, 2016.

4 Adopted by the PCAOB, June 1, 2017: https://pcaobus.org/Rulemaking/Docket034/2017-001-auditors-report-final-rule.pdf

5 Note: Recently completed and active projects of the IAASB include ISA 315 (Revised 2019), the three Quality Management projects, and proposed ISA 600 (Revised). In addition, the Audit Evidence and Technology workstreams of the IAASB are focusing on audit evidence related issues throughout the ISAs as driven by technology, among other factors, and on developing and issuing non-authoritative guidance material that addresses the effect of technology when applying certain aspects of the ISAs. For Audit Evidence: https://www.iaasb.org/consultations-projects/audit-evidence For Technology: https://www.iaasb.org/consultations-projects/technology

6 For example, ICAEW’s “three pillars” framework contemplates additional, or bespoke, assurance engagements beyond the required statutory audit: https://www.icaew.com/technical/thought-leadership/audit-and-assurance-thought-leadership/user-driven-assurance-fresh-thinking

7 IFAC Point of View: Enhancing Corporate Reporting: https://www.ifac.org/what-we-do/speak-out-global-voice/points-view/enhancing-corporate-reporting

2. The Right People

High-quality audits depend on individuals, acting in the public interest, with the experience, integrity, independence, professional judgement, and skills commensurate with a high-quality audit. There is no more important factor. It is therefore vital that audits be conducted in an environment that attracts, develops, and retains the best talent while adhering to the highest ethical standards.

- The increasing complexity of businesses and accelerating reliance on technology are driving the need for firms that perform audits8 to hire more specialized professionals. IFAC believes the multidisciplinary business model—which allows for specialists with diverse skills (e.g., risk advisory, information technology, tax, etc.) to operate within one firm—best attracts, develops and retains these professionals. Initiatives to limit multidisciplinary firms (e.g., “audit-only” firms) would reduce the ability to hire and retain this talent pool, resulting in a significant negative impact on audit quality.9

- As audit evolves, so must the educational and learning / development requirements of professional accountants. IFAC encourages Professional Accountancy Organizations (PAOs) to continue to coordinate and facilitate a dialogue between educators and employers (both firms and business) so that the skills and competencies learned by professional accountants best match the skills required for audit and assurance services of the future. We also encourage PAOs to ensure professional accountants have access to relevant, high-quality continuing education and certification programs, specifically including ones for the provision of audit and assurance services to the most complex global companies. It is vital that education take full account of the growing need for technological competence, forensic accounting, and fraud awareness.

- The audit profession is based on fundamental ethical principles—supported by the International Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants, including International Independence Standards (the IESBA Code)—that must be central to the “DNA” of every audit firm.10

- IFAC believes that high-quality audits require experienced and professionally-trained auditors who can apply professional judgement and professional skepticism. Auditors must approach engagements with a questioning mind, being alert to conditions which may indicate possible misstatement due to error or fraud.11

- Diversity within the profession serves the public interest and drives diversity of perspective and experience, which promote high audit quality. IFAC encourages firms to reflect diversity in their hiring practices and PAOs to promote diversity policies in the profession. Importantly, audit firms and audit stakeholders also benefit from bringing a diversity of professional backgrounds to bear in audit and assurance engagements.

- IFAC believes that there is a meaningful link between the profession’s ability to hire and retain the right people on the one hand and the regulatory approach and public discourse on the other. An inappropriate regulatory approach can create a regime of undue personal risk and be a disincentive for the best and brightest to commit to being auditors.

8 “Firms that perform audits,” “audit firms,” or “firms” refer to professional organizations offering audit, assurance, and other professional services.

9 Audit Quality in a Multidisciplinary Firm, What the Evidence Shows, September 2019: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/files/Audit-Quality-in-a-Multidisciplinary-Firm.pdf

10 The International Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants, including International Independence Standards: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/files/IESBA-Handbook-Code-of-Ethics-2018.pdf

11 ISA 200 – Overall Objectives of the Independent Auditor and the Conduct of an Audit in Accordance with International Standards on Auditing: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/downloads/a008-2010-iaasb-handbook-isa-200.pdf

3. The Right Governance

Achieving high-quality audits is dependent on a well-functioning ecosystem of participants from the audit profession as well as from governing bodies, directors and management. The right culture—starting with the tone at the top—and right oversight are critical to achieving a high-quality and high-value audit.

- IFAC believes that the success of an entity, the quality of its reporting, and the quality of its audit depend on a functioning and effective ecosystem of participants—including boards and governing bodies, audit committees, management, the finance and accounting function, investors/owners, internal audit, external audit, and regulators. Auditors, no matter how skilled or resourced, are unlikely to overcome significant shortcomings in other areas of the ecosystem.

- Audit committees must actively engage in setting the audit plan and be empowered to set engagement terms, including fees commensurate with delivering a high-quality audit. To effectively undertake this responsibility, the qualifications of the audit committee members are critical. They must have appropriate skills, including strong financial and accounting expertise, knowledge of the entity’s operations, and other skills that ensure diverse composition. Audit committees must be independent of management—comprised of independent, non-executive directors.

- Within a reporting entity, professional accountants play a key role in all steps of the reporting process and should support a successful, high-quality audit process—applying their ethical foundation (i.e., the IESBA Code) and technical skills to the preparation of reported information and facilitating communication between boards, auditors and stakeholders. Independent, internal auditors who monitor, review, and provide assurance also play a critical role.

- IFAC believes that firms, regardless of their size, must foster a culture of the highest ethical standards across the entire organization to ensure that the professional accountants they employ act in the public interest. We urge both firms and PAOs to hold themselves and their members to the highest possible ethical standards and appropriately address any lapses.

- IFAC endorses greater transparency and enhanced communication among all participants in the audit ecosystem. We encourage:

- Audit committees to effectively communicate to stakeholders the critical audit decisions, qualifications of the firm performing the audit, important audit findings, issues such as matters of going concern and capital maintenance, as well as how the audit committee evaluates audit quality.

- Firms that audit Public Interest Entities to publish (or enhance) relevant and consistent information that explains how they monitor, measure, and evaluate the quality of their audit and assurance activities (throughout their networks) and demonstrates that commercial considerations do not override quality.

- PAOs to be transparent in reporting their aggregate quality assurance and investigative/disciplinary activities.

- We support the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance as the international baseline and encourage continued focus by national policy-makers on effective implementation thereof. We support Business at OECD’s advocacy in this area as representative of the global business community and reiterate their emphasis on the importance of organization culture, board responsibility, auditor independence, and the risks of over-regulation.

4. The Right Regulation

Regulation plays an important role in calibrating incentives, driving good outcomes, and ensuring that reasonable expectations are met. At the same time, there is the risk that the cost of regulation outweighs the benefits, that regulation can foster low-value defensive behaviors, or can result in unintended consequences such as impeding the ability of firms to attract and retain high quality individuals for their audit practices. That’s why audit needs the right regulation. Right regulation consists of the right supervisory framework, the right standards for auditing, the right business model for firms, and the right approach to auditor liability.

- We believe that any supervisory framework for audit oversight should be designed to drive audit quality through an outcomes-focused approach, based on sound judgement throughout the audit review process, and incorporating a comprehensive understanding of the complexities of achieving high-quality audits—not a check-the-box, enforcement-focused exercise. This requires a prudential approach to regulation—focused not only on holding the audit profession accountable, but also on its long-term viability and impact on economic stability.

- IFAC believes that global audit quality has been enhanced by the development and adoption of standards set by independent, transparent, and publicly accountable boards with the relevant expertise—such as the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) and the International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA). Fragmentation in standard setting would have a negative impact on audit quality. Nevertheless, high-quality audit standards alone are not a sufficient condition for achieving high-quality audits—the standards must be widely adopted and effectively implemented by well-trained audit professionals.12

- Historically, the global economy has been well served by high-quality audit standards that are applied to all entities in a manner proportionate to their size and complexity. However, IFAC believes there is now an urgent need to address emerging challenges inherent in applying the standards to entities whose nature and circumstances are less complex. Likewise, entities in highly regulated sectors like financial services, who are subject to prudential regulation requirements, may need special-purpose assurance services that supplement the traditional financial statement audit. IFAC acknowledges the need for careful consideration of potential implications and unintended consequences of different assurance options and the importance of maintaining robust standards and audit quality across all entities, large or small.13

- We believe that multidisciplinary firms—offering both audit and other professional services—fill a valuable market need. Specialists working within firms are best positioned to integrate needed commercial and subject matter expertise (e.g., tax, valuations, forensics, fraud, cyber security, etc.) into the audit process,—thereby supporting high-quality audits. Quite simply, regulation that would result in audit-only firms will lead to a decrease in audit quality.14 At the same time, auditor independence—both in fact and in appearance—is essential. Measures to support independence should be robust and effective. Adherence to the principles and standards of the IESBA Code, including the non-assurance services provisions currently under review, promote auditor independence and limit potential conflicts of interest related to providing certain non-audit services to audit clients.15

- IFAC believes that the impact of policy tools such as audit firm rotation or joint audit—the appointment of two firms resulting in one audit opinion—are highly dependent on jurisdiction-specific legal, cultural, historical, and structural factors that must be carefully considered, including an evidence-based analysis of likely impacts. These two policies increase the potential for conflicts of interest and can significantly disrupt relationships between reporting entities and their audit and non-audit service providers. The long-term impact of these two regulatory actions (on a stand-alone basis or in concert) could threaten the viability of the multidisciplinary firm model and ultimately harm audit quality. IFAC does not believe that such policies are globally applicable tools for improving audit quality.

- IFAC supports approaches to auditor liability that are designed to support new, expanded assurance services and encourage competition in the audit market. Auditors need to be held accountable for their actions but should not be held responsible for the actions of others like management or boards and oversight bodies. Accordingly, joint and several liability regimes are out-of-date and regimes that employ features such as proportionate liability and liability caps need to be considered by jurisdictions worldwide.16

12 International Standards: 2019 Global Status Report, page 7: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/files/IFAC-International-standards-2019-global-status-report.pdf

13 IFAC supports the ongoing efforts of the IAASB to explore possible actions to address perceived issues when undertaking audits in less complex entities. See: https://www.iaasb.org/publications-resources/discussion-paper-audits-less-complex-entities

14 Audit Quality in a Multidisciplinary Firm, What the Evidence Shows, September 2019: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/files/Audit-Quality-in-a-Multidisciplinary-Firm.pdf

15 The International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants Non-assurance Services project has the objective of ensuring that all the non-assurance services provisions in the IESBA Code are robust and of high quality for global application, thereby increasing confidence in the independence of firms. See: https://www.ethicsboard.org/consultations-projects/non-assurance-services

16 Legal frameworks in Australia and Germany provide useful examples of where these features have been successfully applied, which should be evaluated in other jurisdictions.

5. The Right Measurement

The term audit quality encompasses the key elements, both contextual and quantifiable, that create an environment which maximizes the likelihood that quality audits are performed on a consistent basis.17 Globally, many thousands of audits are performed annually—in the public interest and in accordance with high-quality international standards for audit and ethics. However, consistent with a commitment to continuous improvement, regulators and the profession “cannot manage what they do not measure.”

- Over 40,000 audits of public listed companies are conducted each year without issue.18 From this perspective, the number of significant audit failures is extremely low. The level of attention given to the auditor’s potential role in a small number of recent corporate failures exaggerates the perception of problems with audit and invites overreaction. However, it is always appropriate to evaluate the root causes of audit deficiencies; IFAC and the accountancy profession are committed to continuous improvement, recognize the negative consequences of any audit failure, and take their public interest role seriously.

- Audits play a crucial role in supporting confidence in capital markets and economic transactions, enabling the global economy to thrive. Audits also help limit corruption and engender a higher level of public trust in institutions.19 Data consistently shows that confidence in markets around the world is high, demonstrating that audit is fulfilling one of its core purposes.20

- We believe that audit quality is complex and difficult to define, but can best be assessed through a multi-factor Framework of Audit Quality.21 This said, IFAC supports audit quality disclosures like the Audit Quality Indicators developed by the Center for Audit Quality in the US and elsewhere, peer reviews, and other initiatives—aimed at communicating a better understanding of audit quality, especially through the incorporation of quantitative, relevant, comparable metrics.22 While AQIs and other quantitative measures must be interpreted in context and are audit engagement-specific,23 the lack of such quantitative audit quality measures makes it difficult to generate comparable data within or across jurisdictions or to observe trends over time.

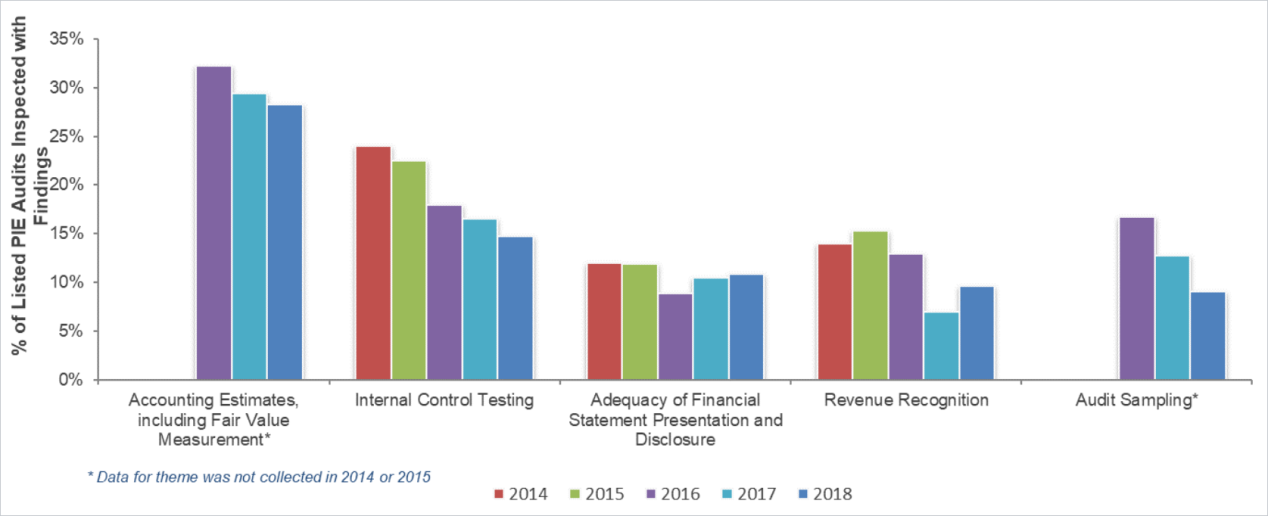

- To the extent quantitative measures of audit quality exist, IFAC believes that, in the aggregate, they point to a positive trend. The number of regulatory findings observed in the high-risk audit files reviewed by regulators continue to decrease globally in all areas of audit24 and represent a very small fraction of the thousands of Public Interest Entity audits conducted in IFIAR jurisdictions. In the US, the largest PIE jurisdiction, the number of actual restatements has dramatically declined.25 In evaluating data on audit quality, it is important to recognize that the number of regulatory findings, regardless of severity, in a sample of high-risk PIE audits cannot be extrapolated across all audits.

- IFAC encourages the profession to demonstrate leadership in better assessing and communicating audit’s value, quality, and success and to actively engage on these issues by providing more and better data that informs policy discussions. IFAC calls on regulators and PAOs to collect, analyze, and publish such data—both aggregate and granular—with the goal of enhancing transparency and promoting higher audit quality.

Trends in Key Audit Areas

2018 Survey Inspection Areas with Highest Frequency of Findings for Listed PIE Audits

17 See Overview of A Framework for Audit Quality, Key Elements that Create an Environment for Audit Quality: https://www.ifac.org/system/files/publications/files/A-Framework-for-Audit-Quality-Key-Elements-that-Create-an-Environment-for-Audit-Quality-2.pdf Other frameworks propose additional factors important to audit quality, for example: Tenents of Quality Audit: https://www.accaglobal.com/content/dam/ACCA_Global/professional-insights/Tenets-of-quality-audit/pi-tenets-quality-audit.pdf

18 Data obtained by IFAC from Audit Analytics for 2019 estimating the number of Public Interest Entities that exist in jurisdictions that submit audit review data to IFIAR.

19 IFAC Point of View: Fighting Corruption and Money Laundering: https://www.ifac.org/what-we-do/speak-out-global-voice/points-view/fighting-corruption-and-money-laundering

20 Center for Audit Quality 2019 Main Street Investor Survey indicates 78% of investors are confident in audited financial information released by publicly traded companies and 83% of investors have confidence in public company auditors. https://www.thecaq.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2019_caq_main_street_investor_survey.pdf In Australia, 87% of investors are confident about the quality of audited financial information: https://www.charteredaccountantsanz.com/news-and-analysis/insights/research-and-insights/how-confident-are-australian-retail-investors In New Zealand, 90% of investors have a level of confidence in the quality of audited financial information: https://www.charteredaccountantsanz.com/-/media/9c7aa3be1fbd49ce8422ac8d70610bb5.ashx

21 A Framework for Audit Quality: Key Elements that Create an Environment for Audit Quality: https://www.iaasb.org/publications-resources/framework-audit-quality-key-elements-create-environment-audit-quality In addition to the IAASB’s approach, ACCA proposes additional factors that determine audit quality. See: https://www.accaglobal.com/content/dam/ACCA_Global/professional-insights/Tenets-of-quality-audit/pi-tenets-quality-audit.pdf

22 CAQ Audit Quality Disclosure Framework: https://www.thecaq.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/caq_audit_quality_disclosure_framework_2019-01.pdf

23 Audit Committee guide to Audit Quality Indicators, Chartered Professional Accountants Canada: https://www.icd.ca/getmedia/9ce81e82-dccd-4d87-951e-e3ad03b1a7ab/01769-RG-Audit-Committee-Guide-to-Audit-Quality-Indicators-June-2018.pdf.aspx

24 Data from IFIAR indicates that the percentage of listed PIE audits inspected with at least one finding has decreased from 47% to 37% from 2014 to 2019. At the same time, the number of IFIAR members reporting from their jurisdictions has increased from 30 to 37 members. See IFIAR 2018 Survey of Audit Inspection Findings, page 4, May 16, 2019: https://www.ifiar.org/?wpdmdl=9602

25 The number of reported restatements has fallen to almost a quarter of prior levels (i.e., from 1853 in 2006 to 516 in 2018): https://blog.auditanalytics.com/2018-financial-restatements-review/

Calls to Action

All participants in the audit and assurance ecosystem must act to improve the audit process, the skill-set and mind-set of accounting professionals, the governance activities of companies and firms, the regulations and standards that support entity reporting and auditor behavior, and how audit quality is assessed.

Right Process

- Approach audits as a value-added process and not as a compliance exercise

- Evolve new assurance services to meet the needs of stakeholders

- Embrace the role of technology in audit processes and audit standards

Right People

- Ensure diversity in hiring practices

- Preserve the multidisciplinary business model while safeguarding auditor independence

- Continue to focus on enhancing skills, competencies, and adherence to fundamental ethical principles

Right Governance

- Appoint properly skilled and independent audit committees

- Enhance transparency and communication from audit committees, firms, and PAOs

Right Regulation

- Update audit standards and assurance offerings to keep pace with the needs of both less complex and highly complex entities

- Adopt a prudential approach to regulation

- Reform legal liability regimes to facilitate expansion of assurance offerings

- Apply evidence-based analysis and consider local impacts when evaluating regulatory tools like Joint Audit

Right Measurement

- Improve measurement and reporting of audit quality—by firms, PAOs, and regulators