- English

- | Spanish

The Sustainable Business Group recently published the milestone State of the Apparel Sector Water report for the Global Leadership Award in Sustainable Apparel 2015. The awards take place in conjunction with World Water Week (WWW), the go-to annual event where international experts, practitioners, decision-makers, and business innovators meet to discuss the globe’s water issues.

The Water Scarcity Challenge

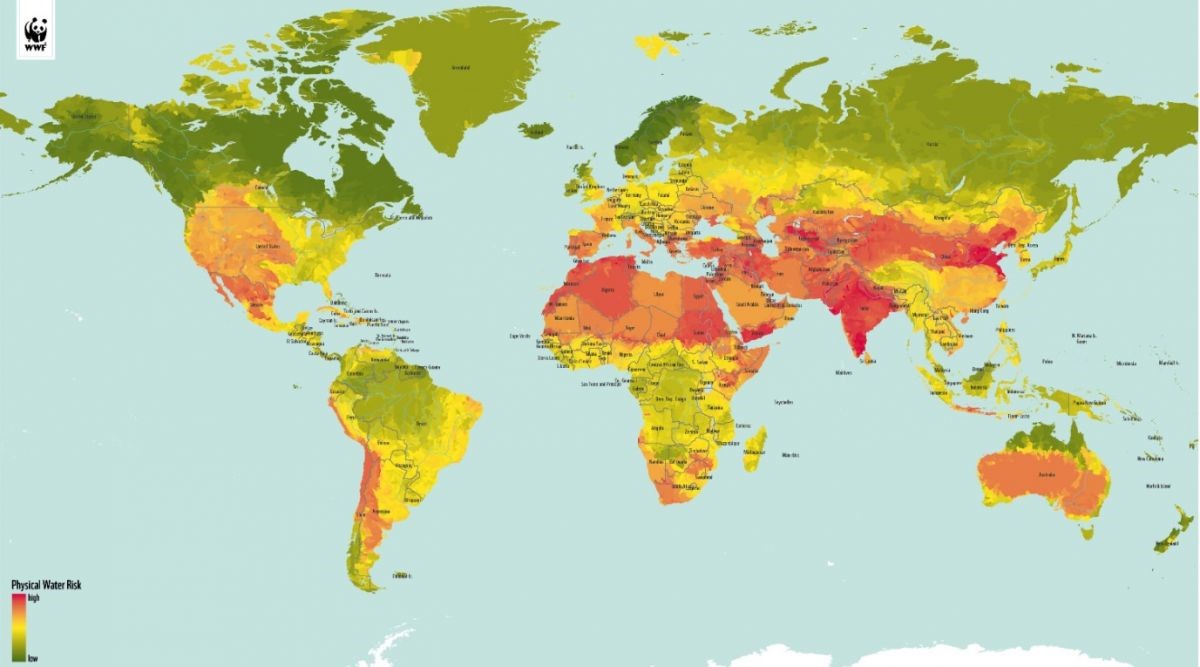

Water is a resource under increased stress, with its management now cited as one of the greatest risks to business continuity and growth. In the big picture, water scarcity has been identified as the number one global risk to society over the next ten years by the World Economic Forum (WEF). From a human rights perspective, access to safe, clean drinking water supplies, hygiene, and sanitation are already risks in many world regions. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF)’s Water Risk Map, which illustrates the countries and regions around the globe that already suffer from high water risk, confirms what the news media is also reporting—that China, India, the US, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Australia, Africa, Turkey, and Brazil are already facing this risk.

Figure 1: Map of Water Risk WWF Water Risk Map ©2014, WWF, Some rights reserved.

Water risk factors include water stress (when local demand for water exceeds available freshwater in the area), drought, insufficient rainfall, flooding, and pollution. Already today, around half of the world's major river basins, home to 2.7 billion people, face water scarcity at least one month a year, and water restrictions are projected to be further amplified by climate change. More than 70 major rivers are already so over-allocated that little of their water reaches the sea, according to the European Environmental Agency’s State of the Environment 2015 global statistics.

Given that the same amount of water is on the planet now as when it was formed, the question to ask is why is water scarcity increasing and what has changed? The answer is rooted in our increased use and pollution of water. The ever-increasing population and urbanization are key features in the growing global demand for water for drinking, sanitation, food, and energy. There is also an inter-connection between what is called the water, food, and energy nexus—the crossover point between the three makes it clear that water demands need to be considered in a systemic way. Climate change adaption also has significant water implications.

By 2030, the global population is expected to be 9 billion with economic growth in emerging markets at 6% and more than 2.5% in well-developed markets. By this time, 4 billion people are expected to live in high water-stressed areas and global freshwater demand will exceed supply by more than 40% if the world continues to follow “business as usual” practices (WEF’s Global Risks Report 2014). For water-intensive business sectors, such as water utilities, agriculture, energy, extractives, chemicals, and textiles, this represents a major resource risk in terms of continued supply, competitiveness, and resilience. Water constraints will increasingly challenge “business as usual.”

Water Management Solutions

So how can we better manage water? What would success in water management look like? Solutions will need to include global, regional, and local perspectives—all the way down to the watershed level. Internationally, the draft UN Sustainable Development Goals for water, set to be finalized in September, see success as a world where there is availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all and where this is seen as a human right. For business, improving water management, as with wider sustainability improvements, requires a mixture of drivers and actors. Drivers include effectively enforced government regulation, market, and financial incentives, such as water pricing (assigning a price to water reflective of its true costs and benefits), and the need for supply chain traceability and accountability for risk and reputation reasons. Industry best practice includes a business model shift from being “water users and polluters” to “responsible water stewards” focusing on protecting and enhancing freshwater resources for all the stakeholders that use them.

Technology innovations for water use/reuse, harvesting, and field- and factory-based improvements are key to rapid, leap-frog change. In terms of water infrastructure, current thinking recommends investment in integrated water resource management solutions for water supply and sanitation suited to local supply and demand into the long term. Collaborative platforms are also important to scaling action and connecting multiple stakeholders. Existing platforms include the UN Global Compact CEO Water Mandate, WWF Water Stewardship programmes, and WEF 2030 Water Resources Group (chaired by Nestle SA, PepsiCo, SAB Miller, and the Coca-Cola Company). Frameworks, such as the Alliance for Water Stewardship (AWS) standard, provide clarity on what a globally consistent approach for responsible water use and management entails.

Some business innovators are taking a lead on water management. For example, Heineken and the UN Industrial Development Organisation operate water stewardship acceleration initiatives for breweries in water scarce countries and regions. The H&M and WWF water partnership is focusing on apparel supply chain water challenges in China and Bangladesh. Levi Strauss & Co has saved one billion liters of water through its Water<Less™ technology (which reduces the water used in garment finishing by up to 96%) and production improvements since 2011. Sasol, the South African energy and chemical company, proactively invested to improve the aging infrastructure of the municipal water catchment they draw from in response to concerns over material water security risks. Even though they only use approximately 4% of the catchment yield compared to other users, investment in the catchment infrastructure improvements provided a lower financial cost for greater long term supply than operating alone within their plant.

Role of Accounting and Finance

Investors and, increasingly, accounting professionals have identified water-intensive sectors as having a high exposure to business disruptions from water-related issues. This can increase production costs and negatively impact profit and loss, and, ultimately, shareholder value. Investors also perceive a potential for stranded assets in light of water scarcity and the growing threat of regulation and markets forcing internalization of externality costs. But water risk also provides financial opportunities. Financial packages such as water funds are increasing in the agriculture sector to support restoration of watersheds, infrastructure development, and sustainable water management. However, investor assessment of water risk is still evolving and financial analysis does not yet systemically include water use and pollution in water stressed regions.

At present, water consumption and pollution is measured in businesses using tools such as Life Cycle Assessment and the Water Footprint. These provide a quantitative measure of water impact at factory or supply chain levels. This information is typically disclosed in corporate social responsibility (CSR) or integrated reports, where material to the business.

Awareness of materiality of water risk is growing. For example, 68% of respondents to the 2014 CDP Water Program questionnaire reported that water poses a substantive risk to their business (questionnaire results available online); 22% of respondents reported that water-related issues could limit the growth of their business and, of these, one-third expected that constraint to be felt in the next 1-2 years.

Translating this information into management accounting, reporting, and financial environmental social and governance (ESG) applications is still relatively new—although growing. Beyond socially responsible investors, institutional investors are increasingly asking businesses how they manage water risk. More tools to support businesses and investors assess and quantify their regional water risk are emerging. These include the WWF Water Risk Filter, World Resource Institute Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas, and the Water Risk Monetizer developed by Trucost and EcoLab. CPA Australia also recently launched their Australian corporate water reporting assessment in Eroding Corporate Water Reporting?

Challenges and Next Steps

While there is growing awareness in business and finance of the critical nature of water scarcity, it is still the elephant in the boardroom for many water-intensive sectors. Raising awareness of the water challenge and shifting mindsets beyond today’s mainly efficiency-based approaches to water stewardship is a key next step. Incentives to drive action—regulatory and market—equal to the scale of the water challenge are still limited and an essential next step for enabling uptake of water management solutions. This is especially the case in emerging markets where water risk is already high. For example, where water pricing exists, it rarely reflects the true value of water and associated costs and benefits. As a result, the price is not high enough to drive the long-term water management solutions required. Beyond water stewardship business models, practices, and incentives, other next steps include investment in water management infrastructure suited to local and regional circumstances, government regulation to shift behavior that is practically enforced, and collaborative platforms to enable scale and integration across stakeholders.

But change is underway in some countries with many of these steps starting to be implemented. For example, China is a recent highly promoted example of increasingly stringent environmental legislation and enforcement. From January 2015, China’s environmental protection law imposed stricter daily fines for pollution across a range of high-water using and polluting sectors, including energy, mining, and textiles. In addition to this strong regulatory enforcement approach, infrastructure developments for water supply, improving effluent treatment, and financial incentives (such as water tariff increases) are a key focus. The Chinese government’s approach is focusing on “three red lines” on water—pollution, use, and efficiency—to shift from a pay-to-pollute to “polluter pays” regime. Import tariffs on water pollution treatment technology have been reduced to incentivize their installation. This new regime is a step change for China, and poses a risk to those who cannot comply and an opportunity to the innovators who can.